Norman Eppenberger and Dr. Maximilian Richter have published a study in the journal European Transport Research Review which provides insight into the opportunity offered by shared autonomous vehicles (SAVs) to improve urban populations’ spatial equity in accessibility. It provides a concrete implementation model for SAVs set to improve equity in accessibility and highlights the need of regulation in order for SAVs to help overcome identified spatial mismatches.

What? SAVs can improve the socio-economic well-being of European Urban Populations

So What? To improve socio-economic well-being, regulation and quantitative analysis are necessary to pinpoint areas where SAVs are beneficial

Now What? Regulators and politicians should foster the introduction of SAVs in areas that are worse of in terms of educational attainment and income

In sight of the multiple lockdowns in response to the coronavirus pandemic the idea of self-driving vehicles has become ever more attractive. Just imagine your groceries and online shopping to be delivered by a driverless car. Moreover, autonomous vehicles (AVs) could be employed to deliver more fragile medical equipment or even patients, putting less people at risk of infection. Certainly, these are very peculiar images and hopes, partially restrained to these pandemic years. However, the question of whether AVs bring benefits to the environment and society are increasingly being discussed in literature. Norman Eppenberger and Maximilian Richter have contributed to this research by affirming that shared AVs (SAVs), can contribute to increasing social equity and increased socio-economic well-being in European cities.

Accessibility and social equity and socio-economic well-being Nowadays most countries “transport policies generally aim to improve accessibility and reduce the negative impacts of motorised transport” (Lucas, van Wee, & Maat, 2016, p. 474). Thus, accessibility has become a central concept in spatial and transportation planning (Geurs, Patuelli, & Dentinho, 2016, p. 3).

Geurs & van Wee, (2004) “define accessibility as the extent to which land-use and transport systems enable (groups of) individuals to reach activities or destinations by means of a (combination of) transport mode(s)” (p. 128). The authors also identify four components of accessibility in the literature: (1) land-use, (2) transportation, (3) temporal and (4) individual (Geurs & van Wee, 2004). Every component of accessibility can be distributed inequitably, and in turn, transportation and spatial planning policy affect equity in accessibility and cause socio-economic developments.

However, will AVs also have a positive effect on social equity and even increase populations’ socio-economic well-being?

In order to provide an answer to this question, the authors relate accessibility to shops in the four European capitals Berlin, London, Paris and Vienna to three wellbeing indicators: educational attainment, yearly income and the unemployment rate. More precisely, the authors compare how many shops are accessible within 30 minutes by car and how many are accessible by public transportation for the inhabitants of the four cities’ districts and see if these underserved districts are also the poorest neighbourhoods.

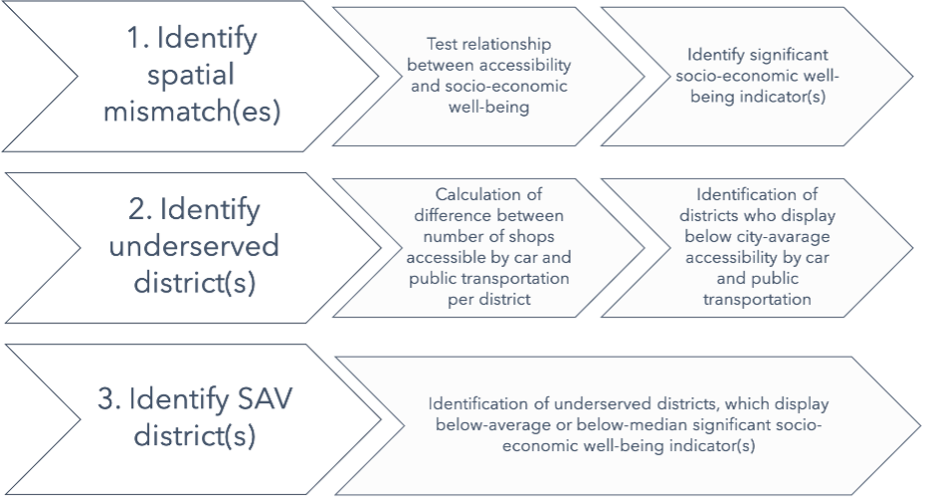

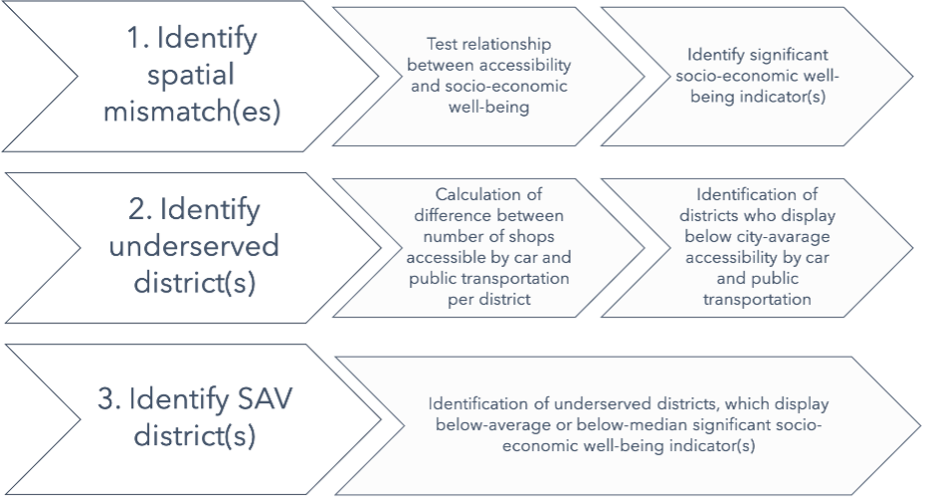

The authors 3-step model provides an overview of how city-districts, in which SAVs could aid to improve accessibility and the well-being of their inhabitants, are identified:

In regard to Step 1, the authors evidence positive effects of educational attainment on accessibility in all four cities. Thus, the higher is one’s educational attainment level, the better one is connected (number of shops accessible within 30 minutes both by car and/or public transportation), and vice-versa. Similarly, yearly income showed effects on accessibility in London and Vienna and an increasing unemployment rate negatively related to accessibility in Paris and Vienna. These thus provide evidence for high-level spatial mismatches in these European capitals.

Do SAVs always improve social equity and socio-economic well-being?

Knowing the great promises brought along by AVs discussed above they certainly may seem like the ideal solution to increase accessibility. Notwithstanding, the authors argue that AVs and SAVs can only stem benefits to underprivileged households and districts if they are introduced alongside policies to overcome barriers of access (see STEPS model created by Shaheen et al. (2017) and adapted STEPS model by Fleming (2018)). For example, there are technological and economic barriers for low-income populations, given that many do not own a smartphone or have sufficient data-packages to take advantage of SAVs. Implementing and regulating the offering of autonomous vehicles in underprivileged neighbourhoods therefore does not secure improved accessibility straight away, even if regulation is imposed that demands shared-mobility providers to implement varied pricing schemes, or if city governments subsidize SAVs for underprivileged populations. Moreover, and most importantly SAVs must be applied in districts that are underserved by public-transportation as highlighted by Step 2 in order to be complementary to existing offerings.

Finally, in Step 3, the authors showcase districts in all four cities that are under-privileged and could improve their accessibility and potentially their socio-economic well-being through the deployment of SAVs. The authors highlight the districts in which SAVs promise to improve accessibility and socio-economic well-being in graphs as exemplified on the left. In the example graph, SAVs only promise to improve socio-economic well-being in district dx, since public transportation already offers greater accessibility than car travel in districts dy and dz. The latter also showcases above-average wellbeing indicators.

In result, the authors identify 8 of the 20 arrondissements in Paris; 5 of 12 Bezirke in Berlin; 7 of the 33 London boroughs; and 7 of the analysed 15 Gemeindsbezirke in Vienna, as SAV-districts. The greatest opportunity for improving accessibility and the socio-economic well-being of city inhabitants through the deployment of SAVs is offered in Vienna, where low-education districts could improve their accessibility by approximately 50% in comparison to the city median accessibility. In Paris, SAVs offer the opportunity to improve accessibility by 30% and in London between 12% to 25% in the identified SAV districts in comparison to the relative measure of city median accessibility.

What do we know now?

- The arrival of AVs and SAVs do not necessarily have to lead to greater accessibility, social equity and socio-economic well-being

- The planification and the deployment of AVs and SAVs needs to be planned, as these new technologies bring many benefits, but could also further marginalize underprivileged populations

- AVs and SAVs are complementary to existing transportation systems and their deployment should take existing transportation systems and accessibility into account

- It is important that the deployment of SAVs is targeted in city areas that are in need of improved accessibility and are underprivileged

References

- Geurs, K. T., Patuelli, R., & Dentinho, T. P. (2016). Accessibility, Equity and Efficiency. Challenges for Transport and Public Services. Edward Elgar. (University of St. Gallen Main Library QR 800 G395 A1).

- Geurs, K. T., & van Wee, B. (2004). Accessibility evaluation of land-use and transport strategies: Review and research directions. Journal of Transport Geography, 12(2), 127–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2003.10.005

- Lucas, K., van Wee, B., & Maat, K. (2016). A method to evaluate equitable accessibility: Combining ethical theories and accessibility-based approaches. Transportation, 43(3), 473–490. doi: 10.1007/s11116-015-9585-2

Kontakt

Norman Eppenberger

Maximilian Richter, maximilian.richter@unisg.ch

Norman Eppenberger and Dr. Maximilian Richter have published a study in the journal European Transport Research Review which provides insight into the opportunity offered by shared autonomous vehicles (SAVs) to improve urban populations’ spatial equity in accessibility. It provides a concrete implementation model for SAVs set to improve equity in accessibility and highlights the need of regulation in order for SAVs to help overcome identified spatial mismatches.

What? SAVs can improve the socio-economic well-being of European Urban Populations

So What? To improve socio-economic well-being, regulation and quantitative analysis are necessary to pinpoint areas where SAVs are beneficial

Now What? Regulators and politicians should foster the introduction of SAVs in areas that are worse of in terms of educational attainment and income

In sight of the multiple lockdowns in response to the coronavirus pandemic the idea of self-driving vehicles has become ever more attractive. Just imagine your groceries and online shopping to be delivered by a driverless car. Moreover, autonomous vehicles (AVs) could be employed to deliver more fragile medical equipment or even patients, putting less people at risk of infection. Certainly, these are very peculiar images and hopes, partially restrained to these pandemic years. However, the question of whether AVs bring benefits to the environment and society are increasingly being discussed in literature. Norman Eppenberger and Maximilian Richter have contributed to this research by affirming that shared AVs (SAVs), can contribute to increasing social equity and increased socio-economic well-being in European cities.

Accessibility and social equity and socio-economic well-being Nowadays most countries “transport policies generally aim to improve accessibility and reduce the negative impacts of motorised transport” (Lucas, van Wee, & Maat, 2016, p. 474). Thus, accessibility has become a central concept in spatial and transportation planning (Geurs, Patuelli, & Dentinho, 2016, p. 3).

Geurs & van Wee, (2004) “define accessibility as the extent to which land-use and transport systems enable (groups of) individuals to reach activities or destinations by means of a (combination of) transport mode(s)” (p. 128). The authors also identify four components of accessibility in the literature: (1) land-use, (2) transportation, (3) temporal and (4) individual (Geurs & van Wee, 2004). Every component of accessibility can be distributed inequitably, and in turn, transportation and spatial planning policy affect equity in accessibility and cause socio-economic developments.

However, will AVs also have a positive effect on social equity and even increase populations’ socio-economic well-being?

In order to provide an answer to this question, the authors relate accessibility to shops in the four European capitals Berlin, London, Paris and Vienna to three wellbeing indicators: educational attainment, yearly income and the unemployment rate. More precisely, the authors compare how many shops are accessible within 30 minutes by car and how many are accessible by public transportation for the inhabitants of the four cities’ districts and see if these underserved districts are also the poorest neighbourhoods.

The authors 3-step model provides an overview of how city-districts, in which SAVs could aid to improve accessibility and the well-being of their inhabitants, are identified:

In regard to Step 1, the authors evidence positive effects of educational attainment on accessibility in all four cities. Thus, the higher is one’s educational attainment level, the better one is connected (number of shops accessible within 30 minutes both by car and/or public transportation), and vice-versa. Similarly, yearly income showed effects on accessibility in London and Vienna and an increasing unemployment rate negatively related to accessibility in Paris and Vienna. These thus provide evidence for high-level spatial mismatches in these European capitals.

Do SAVs always improve social equity and socio-economic well-being?

Knowing the great promises brought along by AVs discussed above they certainly may seem like the ideal solution to increase accessibility. Notwithstanding, the authors argue that AVs and SAVs can only stem benefits to underprivileged households and districts if they are introduced alongside policies to overcome barriers of access (see STEPS model created by Shaheen et al. (2017) and adapted STEPS model by Fleming (2018)). For example, there are technological and economic barriers for low-income populations, given that many do not own a smartphone or have sufficient data-packages to take advantage of SAVs. Implementing and regulating the offering of autonomous vehicles in underprivileged neighbourhoods therefore does not secure improved accessibility straight away, even if regulation is imposed that demands shared-mobility providers to implement varied pricing schemes, or if city governments subsidize SAVs for underprivileged populations. Moreover, and most importantly SAVs must be applied in districts that are underserved by public-transportation as highlighted by Step 2 in order to be complementary to existing offerings.

Finally, in Step 3, the authors showcase districts in all four cities that are under-privileged and could improve their accessibility and potentially their socio-economic well-being through the deployment of SAVs. The authors highlight the districts in which SAVs promise to improve accessibility and socio-economic well-being in graphs as exemplified on the left. In the example graph, SAVs only promise to improve socio-economic well-being in district dx, since public transportation already offers greater accessibility than car travel in districts dy and dz. The latter also showcases above-average wellbeing indicators.

In result, the authors identify 8 of the 20 arrondissements in Paris; 5 of 12 Bezirke in Berlin; 7 of the 33 London boroughs; and 7 of the analysed 15 Gemeindsbezirke in Vienna, as SAV-districts. The greatest opportunity for improving accessibility and the socio-economic well-being of city inhabitants through the deployment of SAVs is offered in Vienna, where low-education districts could improve their accessibility by approximately 50% in comparison to the city median accessibility. In Paris, SAVs offer the opportunity to improve accessibility by 30% and in London between 12% to 25% in the identified SAV districts in comparison to the relative measure of city median accessibility.

What do we know now?

- The arrival of AVs and SAVs do not necessarily have to lead to greater accessibility, social equity and socio-economic well-being

- The planification and the deployment of AVs and SAVs needs to be planned, as these new technologies bring many benefits, but could also further marginalize underprivileged populations

- AVs and SAVs are complementary to existing transportation systems and their deployment should take existing transportation systems and accessibility into account

- It is important that the deployment of SAVs is targeted in city areas that are in need of improved accessibility and are underprivileged

References

- Geurs, K. T., Patuelli, R., & Dentinho, T. P. (2016). Accessibility, Equity and Efficiency. Challenges for Transport and Public Services. Edward Elgar. (University of St. Gallen Main Library QR 800 G395 A1).

- Geurs, K. T., & van Wee, B. (2004). Accessibility evaluation of land-use and transport strategies: Review and research directions. Journal of Transport Geography, 12(2), 127–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2003.10.005

- Lucas, K., van Wee, B., & Maat, K. (2016). A method to evaluate equitable accessibility: Combining ethical theories and accessibility-based approaches. Transportation, 43(3), 473–490. doi: 10.1007/s11116-015-9585-2

Kontakt

Norman Eppenberger

Maximilian Richter, maximilian.richter@unisg.ch